Spotting bias in political surveys

A brief overview of common cognitive biases and how they are used in political polling.

Over the past few months, I’ve heard growing concerns that corporate-backed political action committees aligned with oil and gas, the restaurant industry, and corporate landlords are taking a keen interest in Boulder’s City Council races this fall. That tracks with a poll many Boulder residents received this past week.

Several people asked me if the poll came from the City of Boulder, since the city does send out opinion surveys, like the one used to inform the Community, Culture, Safety, and Resilience tax proposal. That was a public engagement tool.

This wasn’t.

This poll didn’t say who was behind it, but it didn’t come from the city. And the nature of its questions suggests it was designed to influence our perceptions of Boulder and test which messages might divide us.

Polls like this can easily cost tens of thousands of dollars, more than any candidate will spend in this fall’s city council race. That kind of investment suggests someone is preparing to shape the narrative around our elections. It’s worth asking who benefits, and whether their goals align with Boulder’s values.

Let’s break down the problems, so we can be prepared for some of this misleading messaging.

What types of biases were in the poll?

Legitimate surveys are careful to avoid:

- Biased or leading questions (phrased to drive a particular response)

- False dilemmas (artificial choices that oversimplify complex issues)

- Unbalanced scales (imbalanced answer options that skew results)

- Order effects (question sequencing that influences later responses)

- Loaded language (emotionally charged terms that provoke fear or judgment)

You’ve likely seen biased polls pushed by special interests at the national level. For example:

- “Some people think abortion is murder” will elicit a different response than “What are your thoughts on abortion?”

- “Would you prefer stricter penalties for speeding, or are the current penalties sufficient?” is a biased way of asking “What do you think about the current penalties for speeding?”

- “Do you want politicians who are kind or honest?” falsely suggests we must choose between kindness and honesty, ignoring the nuance of real leadership.

Legitimate polls also identify who’s funding them. If someone is spending tens of thousands of dollars to shape public opinion, we deserve to know who they are.

Let’s look at some of the questions

(You can find the larger set of questions here.)

Example 1: Response Bias + Loaded Language

Politically speaking, do you think the Boulder City Council is generally…

- Much too radical

- A little too radical

- About right

- Not radical enough

- Completely undecided; No opinion whatsoever

Notice how many options there are for “too radical.” Is it the same as the number of options for “not radical”? Nope. The “about right” option gives the illusion of balance, but the response options are skewed.

That imbalance creates response bias. If people were responding randomly, the unidentified pollsters could claim that 40% of Boulderites think the City Council is “too radical.”

And then there’s the word radical. It’s a term often weaponized by national figures to make people fear progressive cities like Boulder. In polling, loaded language like this can bias responses by triggering strong reactions.

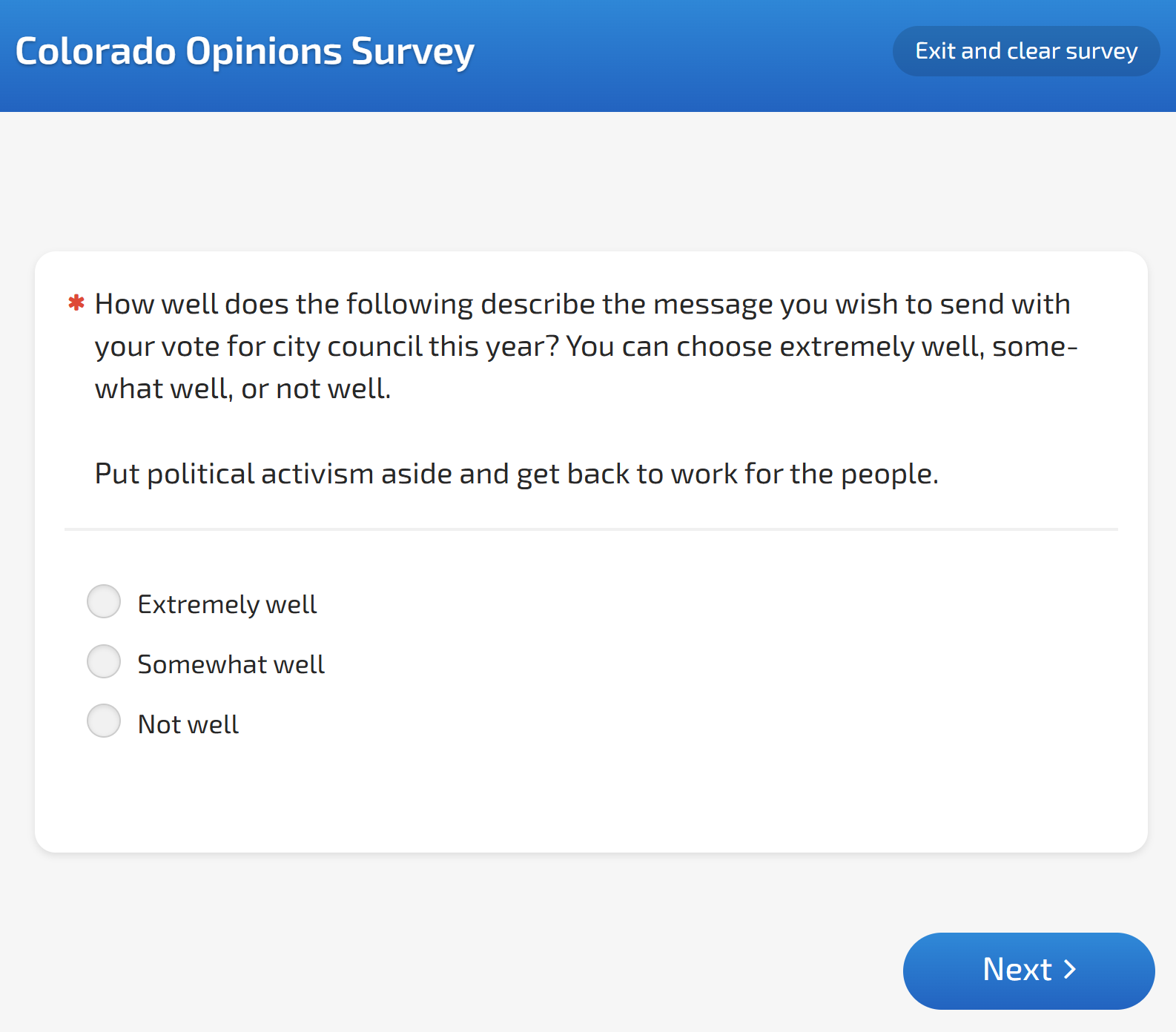

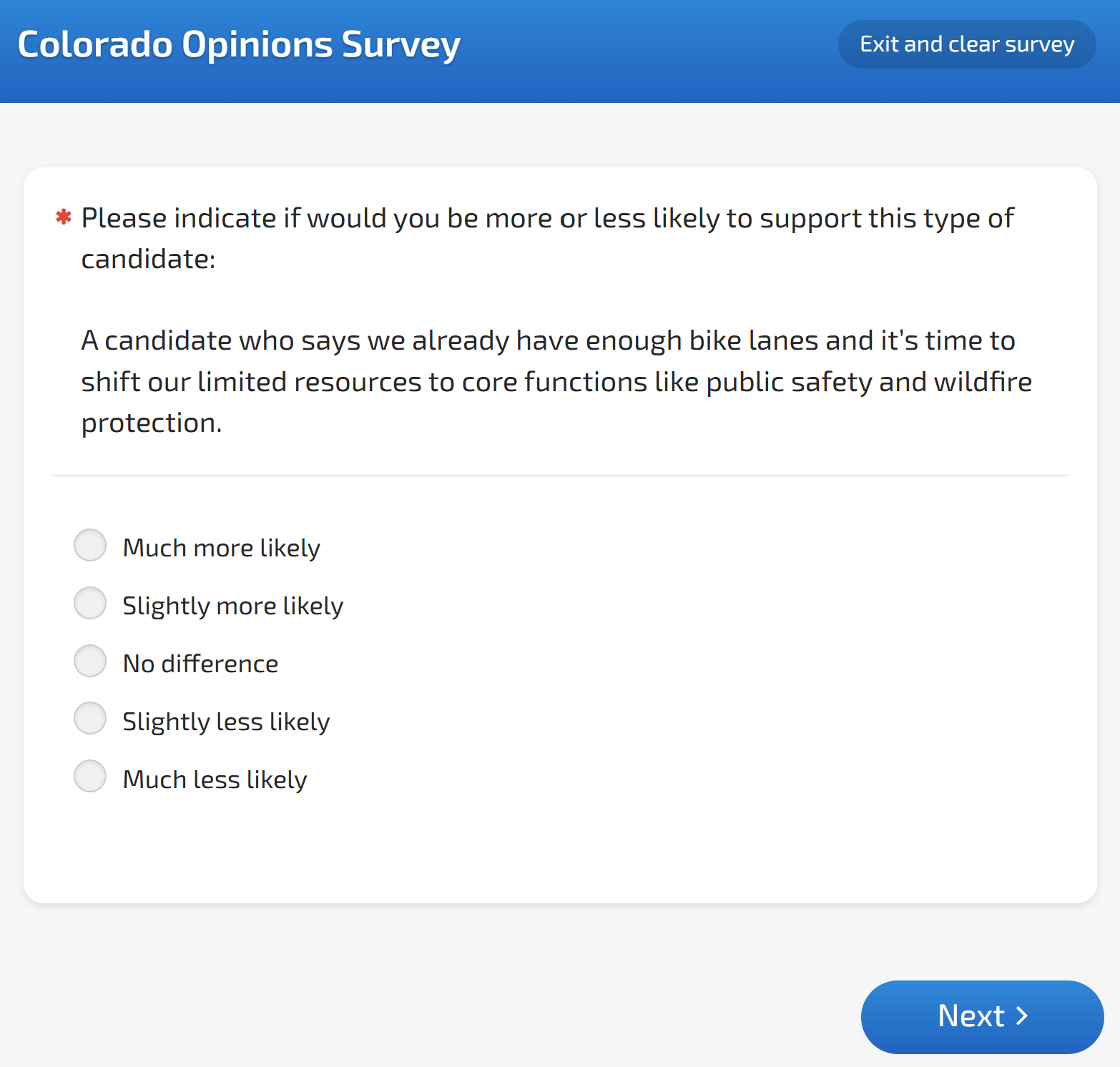

Here are more examples of loaded language and response bias from the poll.

Example 2: False Dilemma

In general, would you prefer a candidate for city council who describes themselves as a pragmatist, or would you prefer a candidate who describes themselves as a progressive?

- I strongly prefer a candidate who describes themselves as a pragmatist

- I slightly prefer a candidate who describes themselves as a pragmatist

- I slightly prefer a candidate who describes themselves as a progressive

- I strongly prefer a candidate who describes themselves as a progressive

- Completely undecided; no opinion whatsoever

This question's responses are balanced in their structure, but the question still presents a false dilemma, suggesting we must choose between practicality and values, as if they can’t coexist.

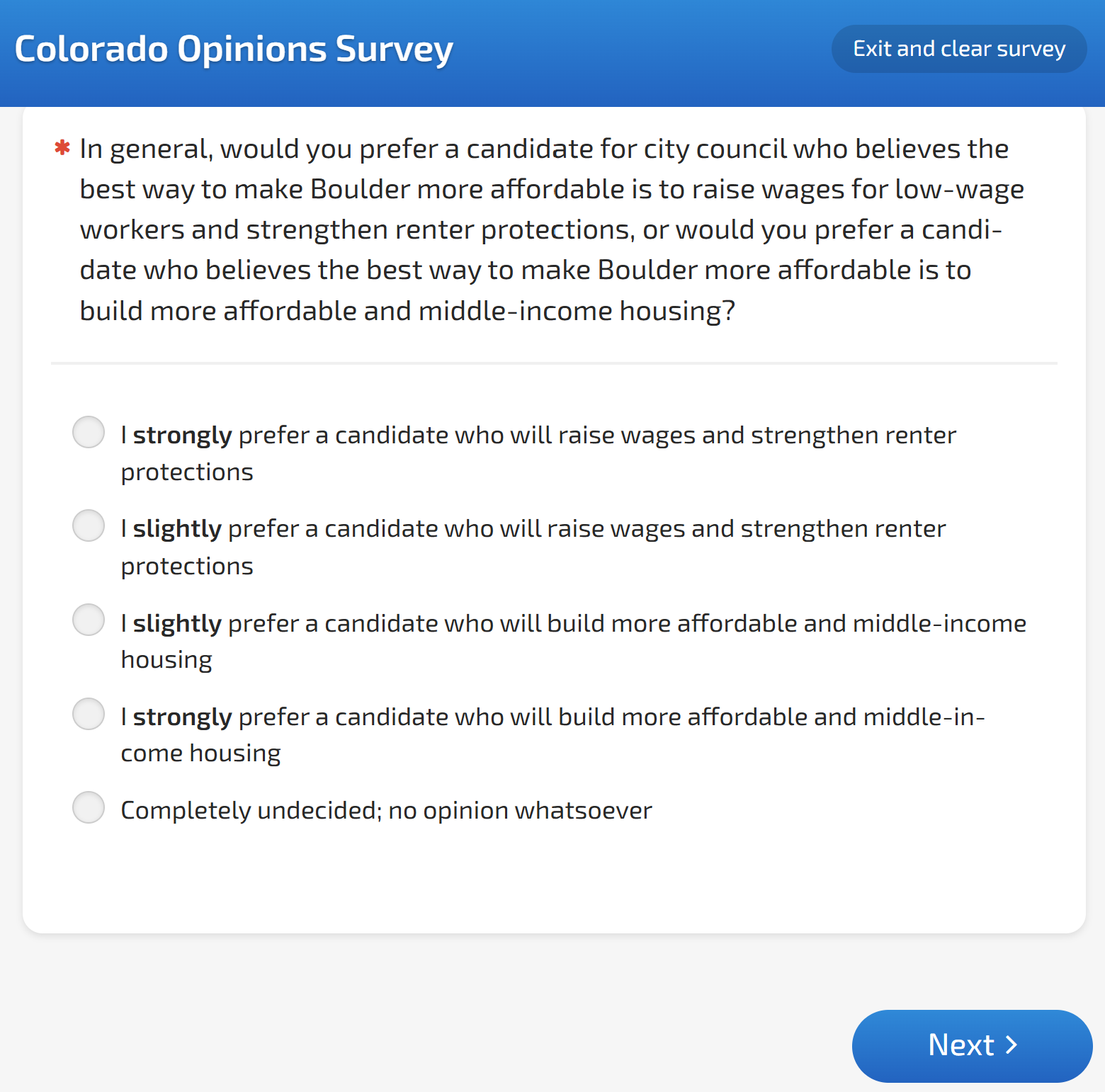

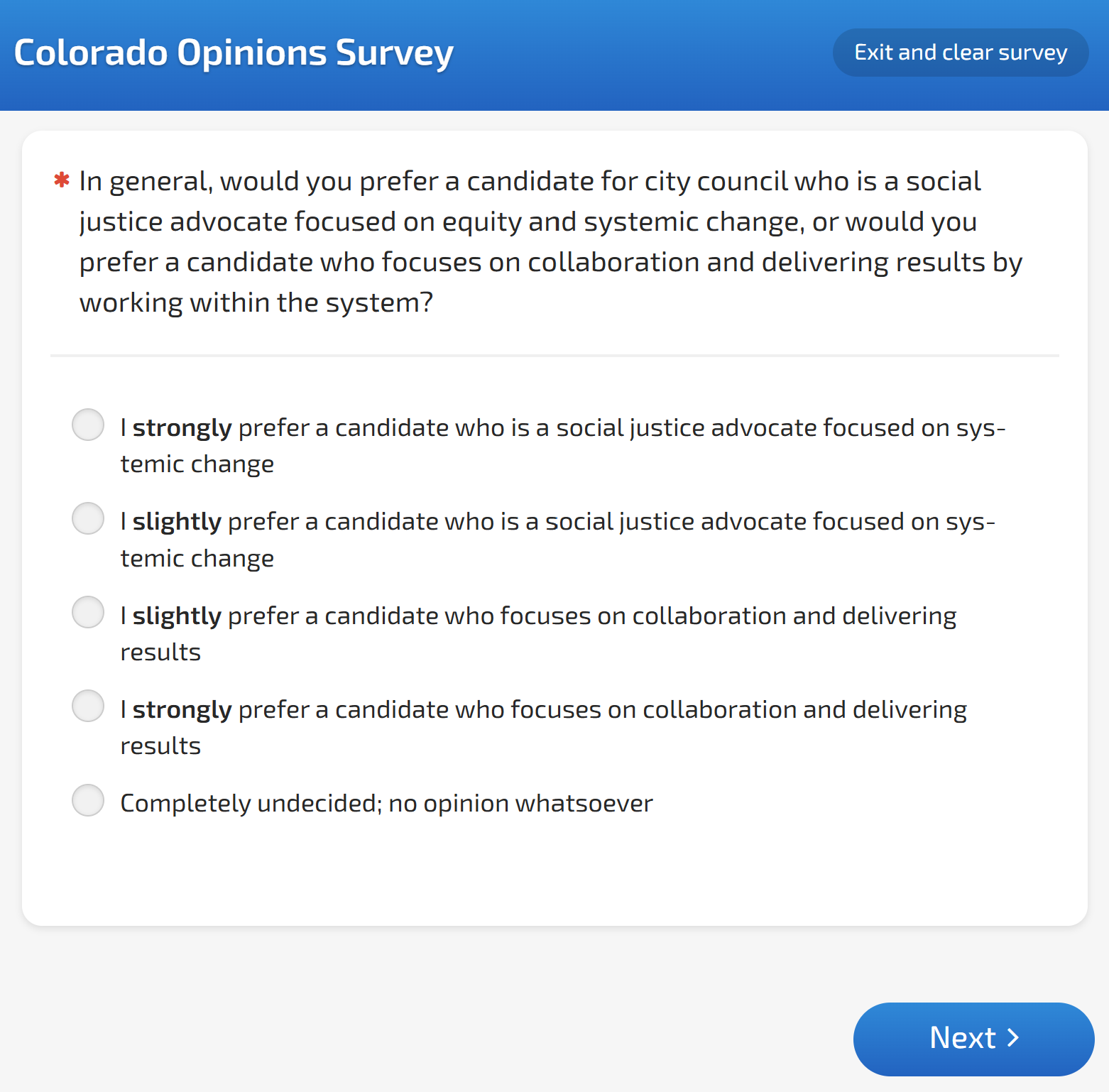

Here more examples of this concept from the poll.

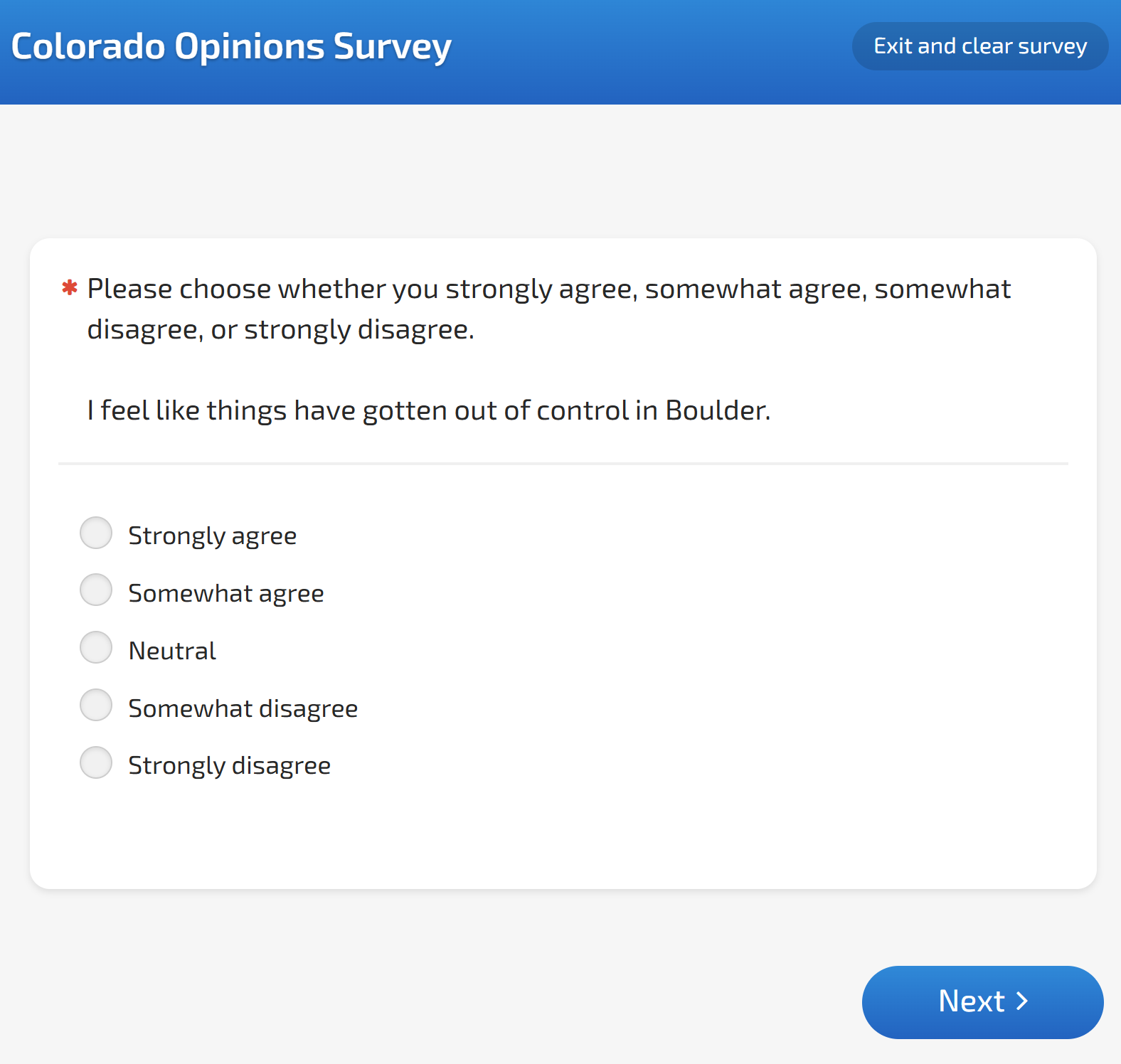

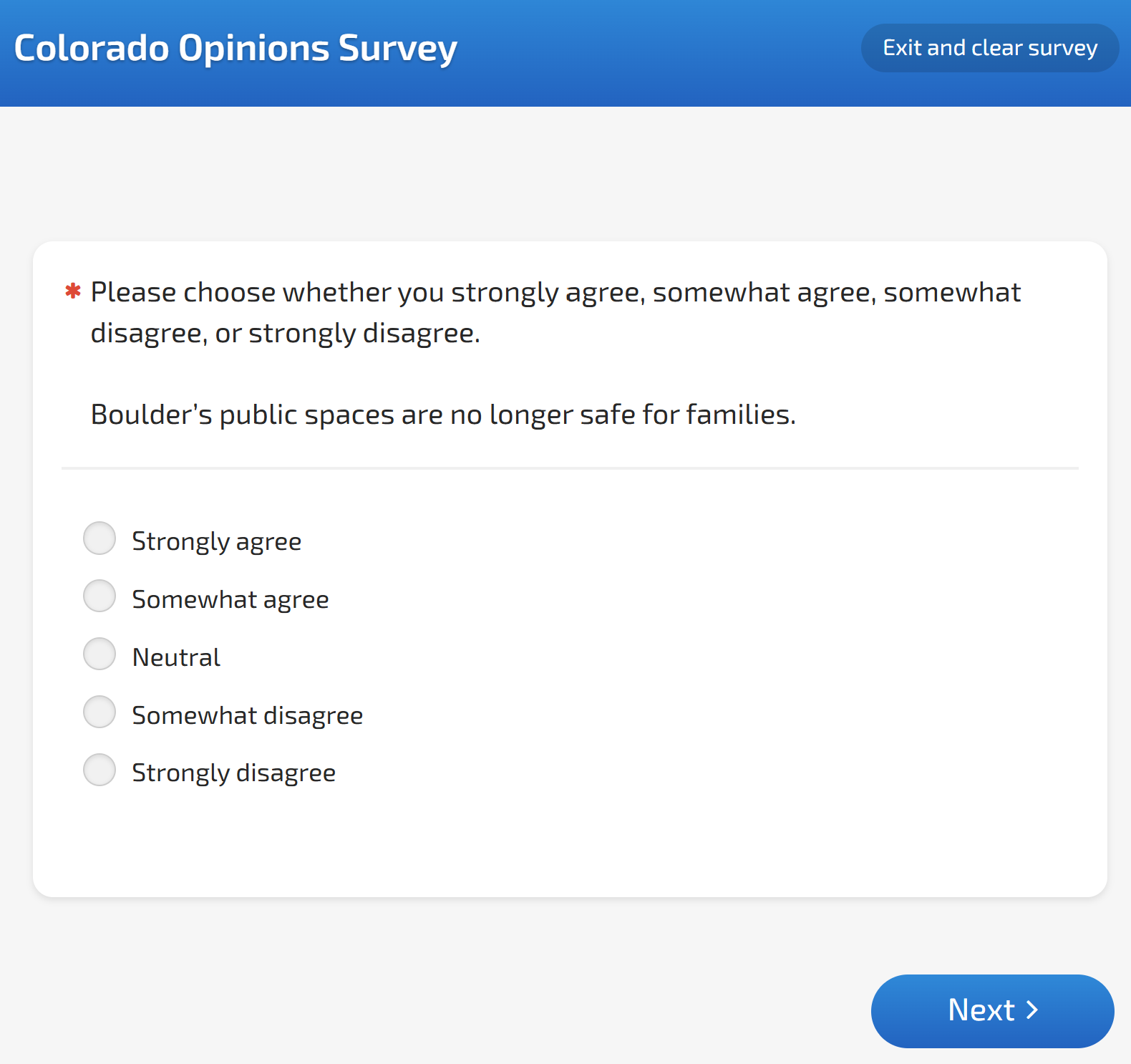

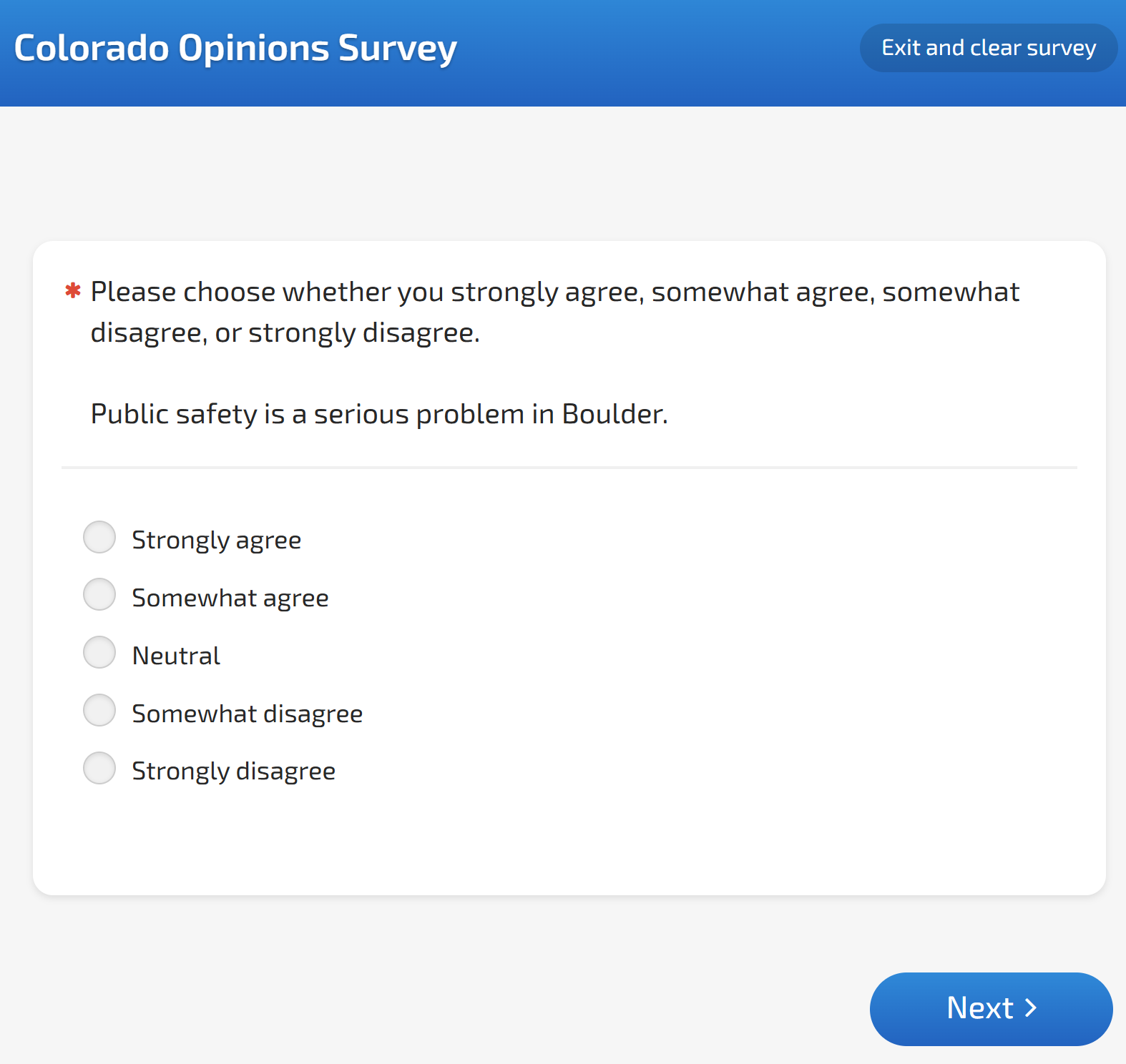

Example 3: Leading Question + Acquiescence Bias

Public safety is a serious problem in Boulder.

- Strongly agree

- Somewhat agree

- Neutral

- Slightly disagree

- Strongly disagree

This is a leading question that primes acquiescence bias (our tendency to agree with statements, especially when they’re framed as problems needing solutions).

It also risks extreme response bias, since emotionally charged topics like public safety can push respondents toward “strongly agree” or “strongly disagree” rather than neutral reflection.

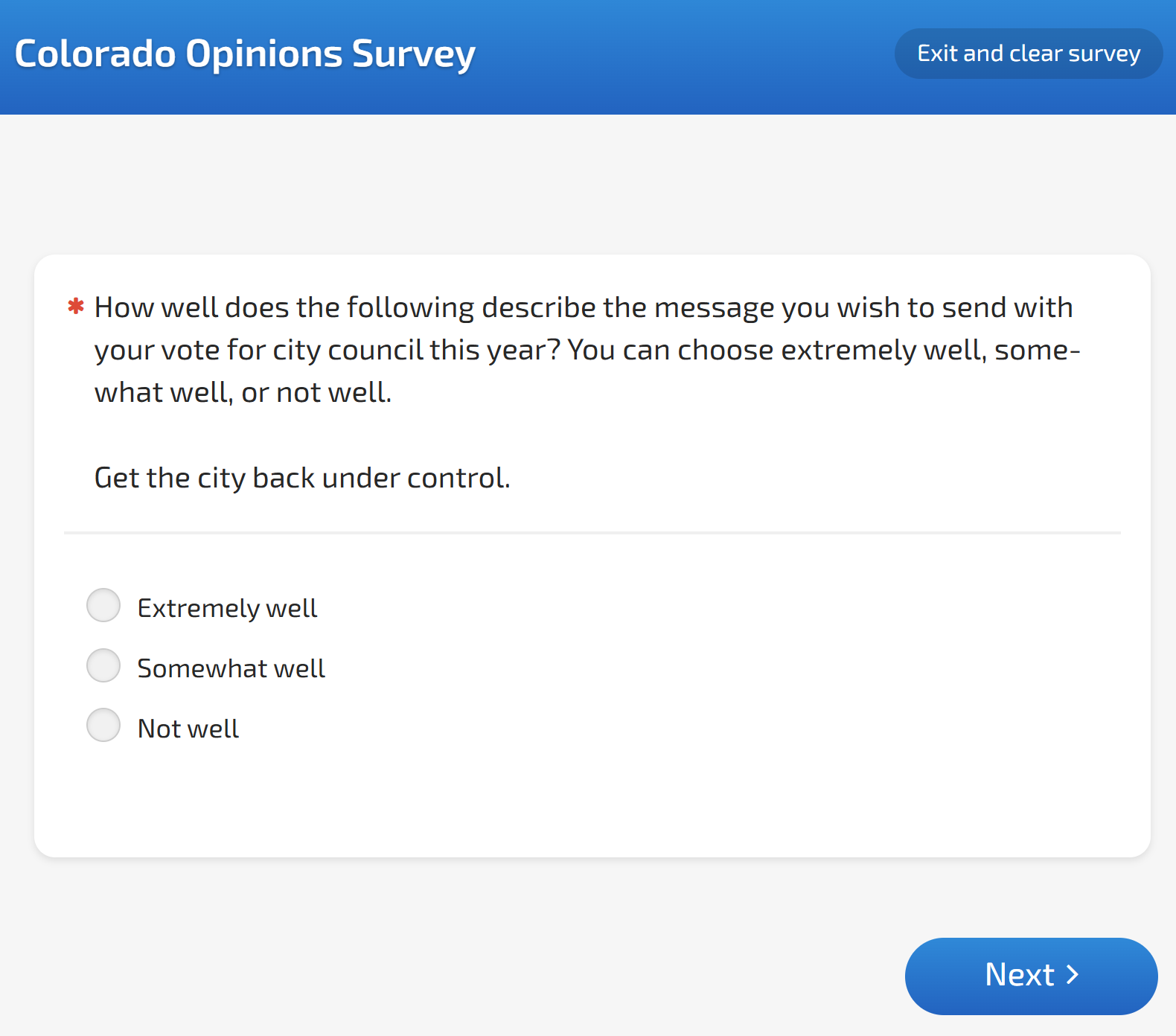

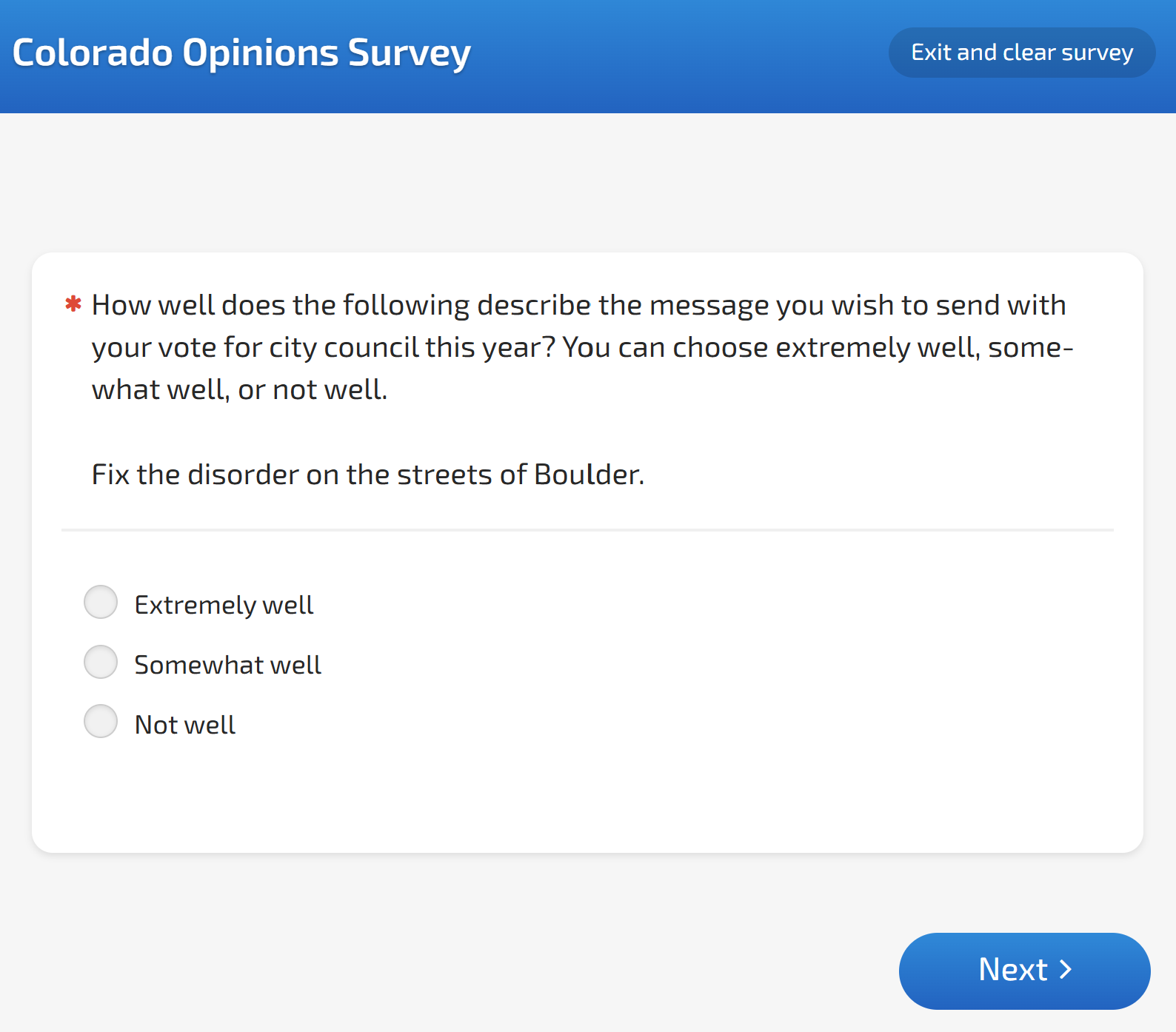

Here are more examples of leading questions from the poll.

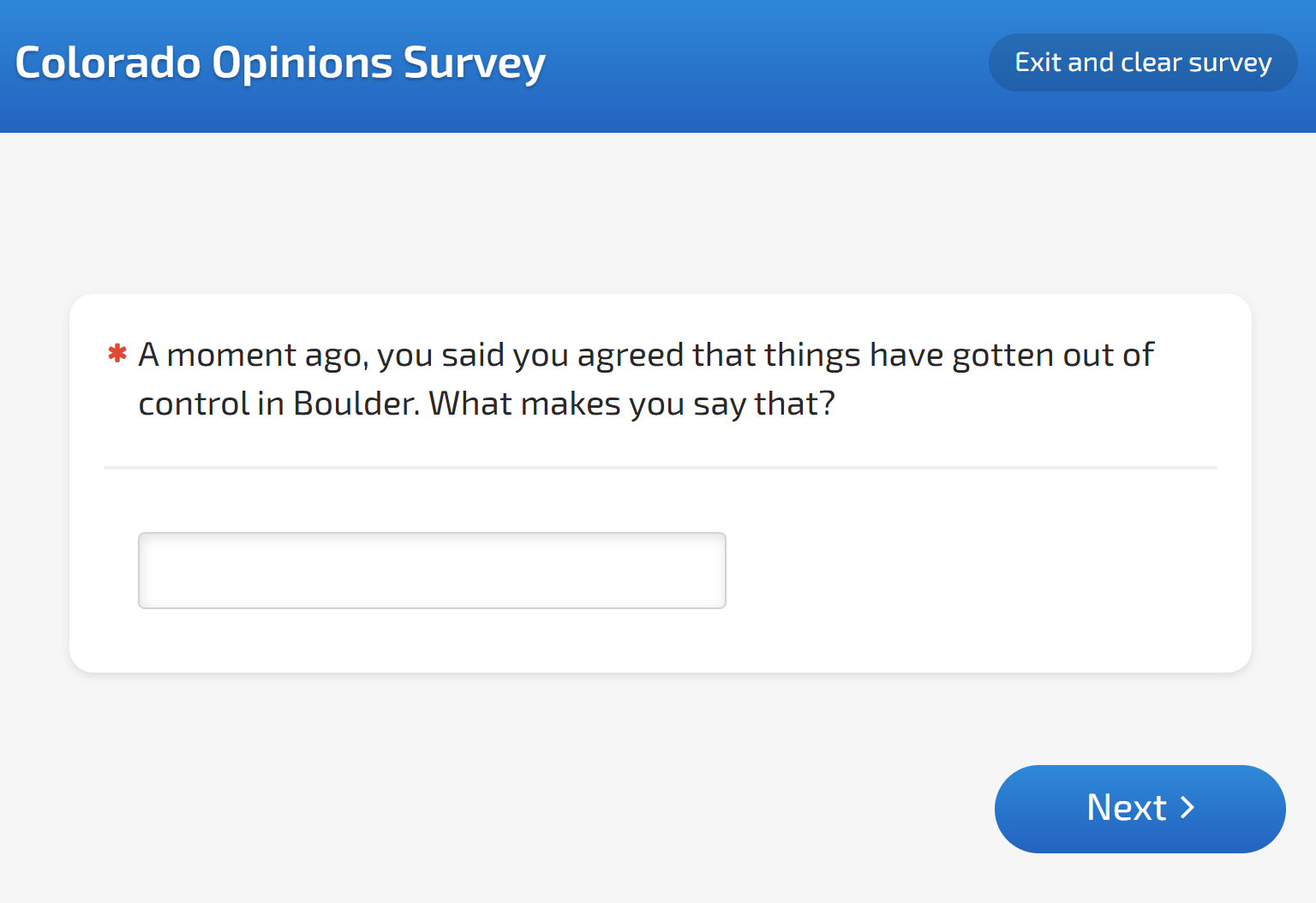

Example 4: Order Effects

Throughout the survey, there were multiple questions related to disorder and crime, despite the fact that most crimes are down, thanks to Boulder’s proactive policing model. When questions are sequenced to repeatedly emphasize a theme, they can create order effects that influence responses to later questions.

Why These Distinctions Matter

Political polling is often used to shape opinions or gather data that can be used to misrepresent facts. When questions provoke fear, oversimplify complex issues, or make us choose between multiple things we value, they’re likely testing divisive messages that will be fed back to us in mailers, texts, and social media ads during election season.

Polls like this also cost big money to produce, often more than candidates can raise and spend if they opt in to Boulder’s public matching program. They’re a sign that well-monied interests are planning to spend big to influence our local elections.

What You Can Do

- Trust your instincts. If a question feels manipulative, it probably is.

- Learn about bias. Bias works best when it’s invisible.

- Stay curious. Ask who benefits from the framing, and whether it reflects Boulder’s values.

A true opinion poll seeks understanding. This one appears designed to test which messages might sway us. The more we understand how our cognitive biases work, the better equipped we are to think critically and make logical decisions.

Learn More

False dilemma. (Retrieved August 18, 2025). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/False_dilemma

Fisher, Sarah (2023, April 1). How to write great survey questions (with examples). Qualtrics. https://www.qualtrics.com/blog/writing-survey-questions

Rasinski, K. A., Lee, L., & Krishnamurty, P. (2012). Question order effects. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 1. Foundations, planning, measures, and psychometrics (pp. 229–248). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13619-014

Survey bias types that researchers need to know about. (Retrieved August 18, 2025). https://www.qualtrics.com/experience-management/research/survey-bias

What exactly is loaded language, and how should journalists use it? (2020, November 3). https://newsliteracymatters.com/2020/11/03/q-what-exactly-is-loaded-language-and-how-should-journalists-handle-it/

Writing Survey Questions. (Retrieved August 18, 2025). https://www.pewresearch.org/writing-survey-questions/